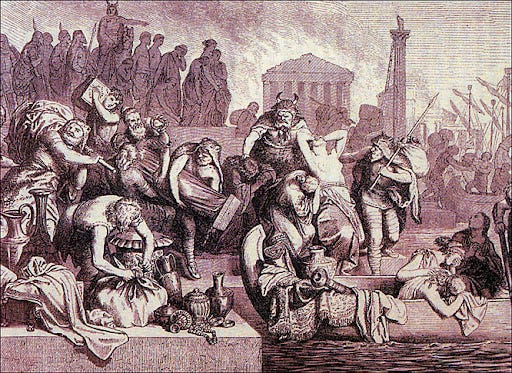

Imagine a warlord sweeps through your village. Some brave young people stand up to him; he mounts their heads on stakes. Some he tortures to death. When he sets his sights on a new conquest, he mails them a whole bag of heads. Some of his enemies hole themselves up in a church full of precious relics, and he burns the whole thing down. He makes a cup from the skull of his enemies and adopts the moniker Bigfuck Blooddrinker.

Bigfuck no doubt enjoys all this, but it has a strategic logic to it as well. The more people know about his tendency to cruelty, revenge, and willingness to carry out threats (even when expensive, as in the case of the relic-laden church), the more those threats work as motivators. If Bigfuck says he’s going to kill your whole family if you don’t bring tribute, you will bring the tribute. If someone goes around saying actually Bigfuck is a big softy and that’s all talk - well, I wouldn’t want to be a part of that guy’s family.

Compare this to the following:

The police in rich countries arrest people, then the courts determine their likelihood of having committed a crime, then the prison system metes out punishment. People of a more liberal bent, who want standards for guilt to be higher and punishments weaker, emphasize just how bad these punishments are, while those who are more law-and-order in orientation emphasize just how much criminals are “coddled,” let off easy, or not found guilty because of high epistemic standards.

With respect to sexual violence specifically, feminists in the 2010s tended to argue that the epistemic standards of the court system were too low, and that sexual violence can be perpetrated with impunity; they also have emphasized how men (including good-hearted ones!) wield implicit coercive power via “the implication.” Redpill types, who explicitly want a patriarchal arrangement, argued that women wielded total power over men via HR and the court system.

Feminists would also like for women not to be coerced into not having sex by prudish attitudes, and emphasize how those attitudes can be widespread; social conservatives, who want those attitudes to be widespread so women can be encouraged not to have too many sexual partners, tell a narrative of a culture which is literally hellbent on promoting hedonism and promiscuity as positive ideals.

Anti-wokes emphasize how the woke mob will have you fired and despised for thinking differently, and publicize examples of this. Their opponents will downplay the extent of this or simply argue against the coherence of “woke” and “cancel culture” as concepts.

Here I don’t want to address the object level concerns in any of these discourses - just to note the pattern. The proximate goal of coercion is to maintain a reputation for coercion, but in each case the advocates for that coercive power act so as to reduce this reputation and its opponents act so as to accentuate it.

Why might this be?

Sometimes, the people wishing for a decrease in coercive power might not have a problem with the effectiveness of the coercion at all, or even support it; they just want to reduce other harms. Most criminal justice reformers don’t think mugging is a good thing and indeed want people to be scared of doing it; they just think the harms of the punishment are ineffective or self-undermining and produce more harm than they solve.

A more widely applicable reason may be audience duality. If you are King Leopold, when you are presenting yourself to European publics, you have every reason to say that you have no interest in the Congo but philanthropic development, an end to the slave trade, and the saving of souls. But when your agents come to visit each village for its rubber quota, it’s Bigfuck Blooddrinker time. When the chief of police in a liberal city is brought to a public hearing she’ll emphasize the procedural respect for the rights of suspects, cooperation with community policing methods, and so on. When petty criminals are brought in for questioning they’ll be asked rhetorically if they want to do the smart thing or get raped repeatedly in prison. Street criminals and the political class are basically non-overlapping subsets, so this makes perfect sense.

But in the cancel culture case potential coercers, the potentially coerced, and participants in the discourse are more or less coextensive. One can easily imagine a very small and vicious person who writes publicly about how there is no such thing as cancel culture and sends anonymous emails threatening to doxx and ruin recipients lives, or who complains about a culture of mandatory hedonism and also writes anonymous messages to women who jilted him explaining how everyone will reject them as a slut, but I don’t think most participants are like this (though the few that are may exert a disporportionate influence,) and each of their ways of speaking has the tendency to undermine the other.

A third possible factor is that people - at least people enjoying some measure of physical security - just care more about affect than effect in most of these discussions. You publicize how your opponents are vicious and how you are bravely standing up to their coercive power - or how you are benevolent and wield no coercive power at all - because that affiliates you with good against bad. This unconscious virtue signalling is the default unless, like Bigfuck Blooddrinker, you have made evil your good (c.f. the section on “evil people exist.”)

However, I am probably missing some other likely factors that impact this! If you have further guesses (or just examples,) I’d be delighted to hear.

[I don't agree with Bigfuck Blooddrinker's system of government, sure - but, my goodness, does he have a cool name.]

I don't think there's really a paradox here: It benefits everybody to have the most effective coercive strategies they can, but it only it benefits you to _openly_ highlight the effectiveness of your coercive strategies when your coercive power is as absoloute and uncontested as Bigfuck's. Imagine a nuclear deterrence doctrine where the nuclear power loudly and openly proclaimed "If we're attacked we'll retaliate with 1.5% of our nuclear missiles", and constantly had huge internal hand-wringing debates about whether or not to increase this to 1.6%*. Subtly coercive strategies are often effective - but openly, overtly, loudly coercive strategies are usually only effective when the coercion is so total and so devastating that nobody can countenance defying it** - and this is clearly true of Bigfuck Blooddrinker, but not of the feminists/police/wokeists/whoever.

I think if you examine the rise to power of some dictators you can actually see the point of inflection where their power becomes sufficiently total that the optimal strategy for them goes from being subtle about their coercive power to highlighting it.

Why is the optimal strategy so different for people with total power to that for people with limited power? Probably just because there's a big social/political cost to being openly coercive and if you don't have enough coercive power this cost vastly outweighs the benefits you'd get from the coercion. And the amount of coercion it takes to make it worthwhile to accept this cost is pretty close to Bigfuck-level coercion because, whilst we will mostly just let ourselves be subtly coerced to some degree, we really, _really_ don't like being openly told we're being coerced.

(So I guess the solution is clear: put Bigfuck in charge of the feminist movement, law enforcement, campaigns for equal rights, etc. etc.)

*Or to look at it from the other side, imagine how incredibly effective eg. feminists could be at achieving their goals if they were able to threaten _and actually follow-through with_ Bigfuck-style policies; laying waste to their enemies, putting their families to the sword and razing their homes to the ground. Would do wonders for the gender pay gap.

**And sometimes not even then..

Surely this asymmetry between the openly coercive tyrant and the modern is owed partly to the following.

First, since maby if not most people dusapprove of coercion for many purposes, coercive policies will not enjoy broad support to the extent they appear coercive. Covertly coercive policies, on the other hand, might enjoy broad support.

And second, the large diffefence in power between actors seems to warrant the kind of impunity the tyrant shows his victims. Whereas in a liberal democracy few people if anyone can wield power so freely and effectively that they can get away with overt abuse of their power.