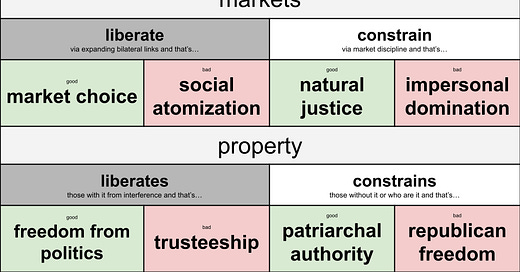

eight moral impulses on markets and property

and why I'm at least somewhat sympathetic to 7/8 of them

In John Holbo’s review of David Frum’s Dead Right - widely and correctly cited as one the single best posts of the old blogosphere - an interesting quadrant is implied. Conservatives have a variety of ambivalent views about capitalism. The least ambivalent are libertarians who appreciate capitalism as an explosion of choice, but from the perspective of many traditional conservatives, precisely this explosion of choice and individualism is something very dangerous. Of course, capitalism constrains as well, which both libertarians and social conservatives can at least in theory celebrate - this is roughly Frum’s argument for NRO-style fusionist conservatism in Dead Right - and which any sensible person can regret as well. So capitalism can be good or bad, because it constrains or liberates, either which way you choose.

Let’s take this from 2×2 to 2×2×2, which risks becoming overly schematic, but which I think may actually help for mapping purposes. We can divide capitalism into markets and property - transferrable property implies the existence of markets and most kinds of market exchange some kind of property, but the link is imperfect, and there are certainly moments like the Antebellum US, where one can identify the Whigs as the “market party” and Democrats as the “property party.” This gives us eight highly recognizable discourses that you’ll see cropping up again and again:

Note that there’s nothing paradoxcial or even particularly suprrising about how markets or money both constrain and liberate. Most social rules do both - we could expand the analysis out to other kinds of governance mechanisms like collective deliberation or deference to established tradition. There’s also nothing paradoxical about celebrating (or rejecting) both the emancipatory and constraining elements of the same rule, both because “whose freedom” may differ (chattel slavery is highly emancipatory, for slaveowners) and because you may consider the tradeoffs worthwhile (you may celebrate the wide variety of choices offered by capitalism while believing that its economic compulsions drive us to industriousness and thrift and that both are good, or resent the economic compulsion to make yourself into a marketable product and find the fifty brands of toothpaste an almost insulting compensation.)

Markets liberate via expanded bilateral links

Markets liberate in the most straightforward way by presenting people with choices. Some of these are trivial, like the numerous very similar brands of consumer products on offer, but others are quite important - consider the opportunity for someone to quit one job for a better one.

…and that’s good (market choice)

Market choice can be celebrated for allowing greater matching and efficiency, but at least as important in the appeal are intangible goods. Modern identity is built upon the crafting of self-identity through consumer choices. Even if you couldn’t raise your wage by switching to another employer, you’d still benefit from the threat of doing so, and you’d still be able to hop over for other reasons.

The same thing that applies to economic partners applies to personal partnerships. It’s dehumanizing (see next paragraph) to treat romance as a pure market, but at least some market-like elements, with people facing many possible options and being able to leave their partners, don’t just free us - that one’s spouse has such freedom offers reassurance that they have chosen, and continue to freely choose, you.

…and that’s bad (social atomization)

But you don’t want romance to be a pure market, do you? Probably not, and if so, it’s because you want these links to be a matter of a highly complex human relationship, in which you can rely richer or poorer, in sickness or in health. You want a moral economy of solidarity in which people are not simply individually weighing up advantage and disadvantage independent of their relationships, and cancelling out any future obligations through exact cash compensation. If my wife and I divide up household labor in some way or another we want it to be because we’re both committed to fairness between us as we succeed on a project (having a life together, raising the next generation) and not just as a case of Coasian bundling.

Circling back to what would otherwise seem like pure economics, note how the protectionist appeal invites this moral economy: people owe a debt of loyalty to their conationals; consumers are “betraying” American (say) companies when they buy Chinese goods, and this can be made via appeal to state action but also directly to consumers.

Markets constrain via market discipline

In the classic model of perfect competition, economic profits drop to zero, and all firms that do not correspond to best practices go the way of the dodo. Market participants, then, are asked to act in the way demanded by the market. (If this is too spherical cow for you, note this only as a tendency, then, and note the ways in which highly competitive markets can start to resemble it.)

…and that’s good (natural justice)

And this is entirely good. Left to their own devices, people are at the mercy of the demands of vague social consensus, or their immediate desires. Bureaucracies reward compliance with some socially legible set of rules, not what actually works. Human discretion about quality, such as gives out literary prizes, is hopelessly corrupt from the get-go. Market discipline demands that you find out what the situation demands and do it, being rewarded if and only if you do what is actually required. God Himself could not be so just.

Anecdotally, I believe this is a significant source of the moral appeal of capitalism to at least one of its mass constituents, the slightly spergy elite tech worker. Such people have a high degree of confidence in their technical skills, a high degree of honesty, and a low degree of confidence in the moral rightness of, or their ability to navigate, the world of fuzzy social consensus. Market discipline holds out the promise of being of government of “laws, not men.”

…and that’s bad (impersonal domination)

But to be governed by “laws, not men” in the ultimate case is for humans not to be self-governing. The “natural justice” appeal is like a genie’s wish granted for anarchism: “by whom shall you be ruled?” “no one!” “very well, you shall be ruled by no one, but you will be ruled.”

On the efficiency side, there’s the matter that markets don’t capture everything we want; on the dignity side, there’s the sense (which I feel too deeply to justify) in which there’s just a value in coming up with our own way of doing things over and above the results. If presented with the option between humans coming up with an imperfect set of laws and an angel giving us perfect ones, there’s some difference large enough in quality that angelic dictatorship would be preferable, but that difference is not zero.

Freddy DeBoer’s list of overoptimized hellscapes is a good survey of instances where people dutifully, objectively following the incentives gradients has caused many systems to suck.

Property liberates those with it from interference

If something is your property, then you get prima facie say over what to do with it. There may be legal or social carve-outs from this, but it is at least the default. You do not have to have a conversation; you can just do the thing that you want.

…and that’s good (freedom from politics)

This is good because it gives people - or at least people with property - some reprieve from having to keep track of what everyone else wants; a sphere of unaccountability in which they can just think about their own affairs. The left is not immune from this: “eight hours to work, eight hours to rest, eight hours to do as we please” is a sort of freesteading on one’s own time. Everyone deserves some time, and a body, and a space, in which they are not really accountable to anyone else.

The petit bourgeois, for their part, have a politics that is dominated by a combination of this and fear of impersonal domination - they value their autonomy, an autonomy that is always under threat both from the government and the impersonal market, leading to right-wing politics. This is not an original observation, but it is one that naturally fits into this overschematic framework here.

…and that’s bad (trusteeship)

But you might say: unaccountability and irresponsibility are bad! People should do the best thing!

Sarah Constantin’s essay on normativity and anti-normativity speaks to much of the tension here. Property is fundamentally about the legal right to dispose of something, while Constatin’s essay is more or less about the expectation to act without being criticized too harshly, but many of the same dynamics apply.

Property constrains those without it

Property is by definition a limitation imposed on those who do not have it. If a field is no one’s property, I may walk through it; if it is someone else’s property, armed men may beat me if I attempt. (Thus, as G.A. Cohen points out, property rights are violations of negative liberty.) If lots of things you interact with are someone else’s property, they hold power over you and can set rules.

…and that’s good (patriarchal authority)

Once can celebrate this, if it allows better rules to be set. In particular, there is a natural affinity between “natural justice” and “patriarchal authority” arguments: if the market naturally allocates property to the best (highest IQ, highest time-preferences, whatever) people, then property allows them to benevolently govern the natural slaves.

This is the only of the eight discursive frames that I reject entirely. There are some people that are in a sense the natural charges of the rest of us, such as the very old or very young, but the amount of power they exercise (~0) is basically unaffected by how much formal authority they have. Among the rest of us, some (such as you, dear reader) are more talented or driven than others (such as me), and these people will naturally carry more influence in a democratic society through persuasion or negotiation or simply showing up - but I’m skeptical that differences in wisdom are so great that we would benefit surrendering to them more power beyond this.

…and that’s bad (republican freedom)

It is bad, all else being equal, to be subject to the power of another.

It is worst to be owned yourself, by another. But having no property and having to sell your labor under the direction of another is also bad. Living somewhere where another can kick you out is bad. If you each have similar power over each other, then you can negotiate deals that benefit both of you, but when they govern you more than you govern them, well, they are going to govern you in a way that benefits them. Information failures (I do not know what you want) and declining marginal utility mean that the benefit to them is less good than the harm to you, in general.